Scott Gillam, Canadian Museum for Human Rights, Canada

Abstract

The latest in modern technology supports the oldest and most human form of communication—storytelling. Artifacts and artworks become tangible touchstones that connect visitors to human rights. Digital experiences through virtual or augmented spaces extend the boundaries of progressive storytelling and education, placing the visitor at the center of an experience. One of the great advantages of leveraging cross-media and non-linear storytelling principles such as VR and AR is the creation of multiple entry points to a particular subject or theme, and using a multiplicity of interactive technologies to find new ways of experiential storytelling—all within the context of the museum. We explore two case studies: The Weaving a Better Future VR experience, which transports the visitor to Guatemala, where they can learn about the lives, history, and culture behind the TRAMA Textiles cooperative in Quetzaltenango and a shop in Antigua called Textiles Colibrí. The shop provides much-needed income for the women artisans who both run the cooperative and produce the textiles for sale there, using their traditional Mayan weaving techniques. The Stitching Our Struggles AR app uses compelling works of art, powerful personal accounts, and augmented reality technology to tell the stories of people who have used art to expose truth and motivate action. Leveraging new participatory experiences has resonated strongly with visitors, and has not only enhanced the museum narrative, but also the creation of narratives by the visitors themselves.

Keywords: storytelling, emerging, technology,digital, experience, virtual

Introduction

The latest in modern technology supports the oldest and most human form of communication—storytelling. Storytelling is at the heart of what we do at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR). Dynamic, interactive exhibits are arranged around human rights themes, using multimedia technology and stunning visuals. Artifacts and artworks become tangible touchstones that connect visitors to human rights; but storytelling and performance make concepts come alive.

Cross-media storytelling allows us to take visitors on a journey that starts inside our galleries and extends across the globe. Digital experiences through virtual or augmented spaces extend the boundaries of progressive storytelling and education, placing the visitor at the center. To best understand the environment for which these strategic opportunities are explored, there are some important considerations that have led the CMHR to be uniquely positioned to take advantage of these types of experiences.

The landscape of an ideas museum

The CMHR is one of the most digitally advanced cultural institution in North America, providing visitor experiences such as interactive kiosks, tables and games, immersive environments, gesture-based interactive exhibits, multimedia presentations, and tours via the mobile app. Over 47,000 square feet of digitally rich mixed-media installations explore the subject of human rights, promoting respect for others and encouraging reflection and dialogue. Dialogue is understood metaphorically in the museum’s approach to experiential design, through traditional museum methodologies as well as technology.

Multiple perspectives inform the human rights stories that are showcased at the CMHR. The museum houses a vast digital collection of recorded oral histories, relayed by people with lived experience of human rights in Canada and around the world. With a collection that is largely digitally based and a predominantly conceptual subject matter, the requirement for storytelling to be multi-modal and responsive to different presentation types is essential.

The museum’s inaugural exhibits, opened in 2014, include over 100 hours of video; four feature films; an immersive multimedia experience; 26 small format films; 37 large scale linear media projections; 512 video clips; more than 250 artifacts and works of art; 2,543 images; two soundscapes; 18 mixed-media story niches; 19 digital interactive elements; 100,000 words of original text; and seven theaters.

To sustain an environment leveraging the semantics and structures of converging technologies, the CMHR’s award-winning Enterprise Content Management System (ECMS) was designed to be flexible, open-sourced, and as modular as possible. This implementation allows technology to be scalable and responsive, allowing the delivery of stories in faceted approaches adhering to principles of inclusive design (Timpson, 2016).

All aspects of the museum and its exhibits were built with inclusive design and accessibility in mind. Inclusive design has been embraced by CMHR in an approach that sets new Canadian and world standards for universal accessibility. Cutting-edge technology, nationwide input from the disability community, and pioneering Canadian research ensure the visitor experience is designed to include the full range of human diversity. When noting the benchmark that CMHR has set for itself, it is important to express that inclusive design is an ongoing activity for the museum in the development and evolution in storytelling and accommodation.

Fostering innovation in storytelling and digital literacy

Sometimes it’s just knowing where to start. Technology selection can get complicated when you overthink things. Emerging technology can transcend storytelling by breathing new life and fresh energy into how visitors engage with meaning.

How do museums compete for space in the public consciousness? As a museum whose mandate is to inspire reflection and dialogue, CMHR finds itself amongst many other institutions with the intent for content to become a third space for the public to form communities around (CAM, 2012). CMHR does not want that third space to be limited to the physical architecture. To fulfill our mandate as a national museum, we need to be active in creating infrastructure that supports the third space virtually as well. Competing in that space is an ever-crowded array of content types, including social media, streaming platforms such as Netflix, and more (Shu, 2015).

To foster innovation in storytelling, we identified the need to cultivate the tools necessary to deliver cross-media storytelling. One of the great advantages of leveraging cross-media and non-linear storytelling principles is the creation of multiple entry points to a particular subject or theme. Selection of key emerging technologies allow us to bring attention to those entry points for multi-generational audiences. In addition, creating such methodologies through technology often provides the necessary hooks for media agencies to publicize or otherwise report stories involving themes and content that the museum is seeking to bring to the public’s attention.

In fall of 2015, creatives from both the linear and interactive production industries had the exclusive and ground-breaking opportunity to work on interactive storytelling thanks to a partnership between the CMHR, On Screen Manitoba, New Media Manitoba, and the National Film Board of Canada. Joined with national and provincial partners, we sent out an open call for local game designers, experience designers, software developers, documentary filmmakers, and writers to take part in the Creation Lab. Over the course of a three-day weekend event, participants explored new forms of storytelling through the creation of digital prototypes for museum installations in response to a specific theme related to human rights.

The objective was to facilitate a hands-on experience that is both collaborative and creative with professional linear and interactive content creators, communicating complex themes through storytelling supported by immersive and interactive technologies.

The resulting application and jury process resulted in a group of filmmakers, artists and interactive media producers gathering for a three-day “hackathon” of meeting, conceiving, innovating, and creating. The goal was to use a multiplicity of interactive technologies—augmented reality, virtual reality, geo-location, and sensor-based multimedia installations—to find new ways of experiential storytelling within the context of the museum.

The idea of putting people of complimentary talents together in a compressed, hothouse, idea-generating environment is not new; but it has always proved effective, and the potential combinations are endless and ever-innovative.

Through hosting an event that reduced the internal pressures that are usually implied by the development of museum exhibitions, we pressure-tested the potential of emerging platforms for immediate consideration. Along with fostering the creative community and providing a professional development opportunity, we increased the digital literacy of our research and curatorial team in the presentation and consideration of these prototypes.

Within the eight months following the lab, we would deliver two experiences influenced by the research and development during the Creation Lab. The first would be a virtual reality experience, followed closely by an augmented reality experience.

Virtual reality: emergence, maturity, and widespread adoption

Years of research and development have led virtual reality into mainstream adoption. For filmmakers, documentarians, and journalists, the combination of immersive video capture and distribution via mobile VR players is experiencing incredible proliferation. The immersion of VR delivery methodologies, when successfully achieved, brings audiences closer to a story than any previous platform (Pitt, 2015).

This version of VR places the tradition of the documentary medium squarely into the hands of storytellers. It provides the ability to transport their audiences into the story in ways unmatched by any previous media device. Each of these factors allows audiences to more richly experience the lives of others. One of the most well-known examples of this type of journalism VR is the New York Times NYTVR app, which last year completed a second distribution wave of Google cardboard headsets to its subscribers (Robertson, 2016).

The increased availability, reduced cost, and technological advances in cameras that can record a scene in 360-degree, stereoscopic video have begun to increase access for museums to begin progressive delivery of VR as an in-gallery and remote audience activity. However, consideration and adoption of VR can still be a challenge for small to mid-size museums.

Empowering an exhibition with virtual reality

In January 2016, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights was preparing to present the exhibition Empowering Women: Artisan Cooperatives That Transform Communities (https://humanrights.ca/exhibit/empowering-women), which was originally organized by the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and is circulated through GuestCurator Traveling Exhibitions. Empowering Women explored how working collectively has enabled women in communities around the globe to support their families, preserve their traditional arts, and transform their communities.

One of the common workflows in accommodating traveling exhibitions for the CMHR is the reframing of themes through a human rights lens, to closer align with the mandate of the museum. Along with reframing or reconsidering of text, we consider what elements exist within an exhibition that will meet our commitment to universal design, accessibility, and digital engagement. Most often this takes place through editing text, and the considerable effort of our research and curation team in partnership with the curators and institutions involved in the original exhibition.

During the research process for this exhibition, CMHR cultivated a relationship with two women’s co-ops, TRAMA Textiles and Textiles Colibrí in Guatemala. CMHR wanted to add a Guatemalan component to the exhibition that would feature these co-ops, in addition to the 10 other locations that were part of the original exhibition.

Equipped with the learning outcomes from the Creation Lab in 2015, this precipitated the decision to send three of our staff to Guatemala for 10 days to film what would become our first virtual reality documentary. In addition to the original Empowering Women exhibition, exploring the opportunity to shoot 360-degree immersive video in Guatemala featuring the co-ops would result in combining physical artifacts, tactile original artworks, and virtual reality. The Weaving a Better Future VR app launched in coordination with the opening of the exhibition, elevating the audiences’ ability to connect to with the women in Guatemala who are featured in the exhibition. This experience offers visitors an opportunity to be placed in a virtual space outside of the museum.

The Weaving a Better Future VR experience transports the visitor to Guatemala, where they can learn about the lives, history, and culture behind the TRAMA Textiles cooperative in Quetzaltenango, and a shop in Antigua called Textiles Colibrí, that provide much-needed income for the women artisans who both run them and create the textiles for sale there with their traditional Mayan weaving techniques, .

Functional design for VR: platforms and pitfalls

During the production phase of story development, the decision was made early on to break the linear elements of the VR into siz segments of approximately two minutes, for a total of 12 minutes. With the understanding that most of our audience would be experiencing VR for the first time, we chose to have a two minute introduction section that would help onboard and acclimatize the visitor, followed by four chapter selections and an “outro” selection. Visitors would then have more control over their preferred length of experience.

In the evaluation of software combined with ease of use, the Samsung Gear VR powered by Oculus was identified as best suited for our initial offering to deliver a VR experience. Producing the VR as a Gear VR app would provide a readily available mobile-handset based hardware experience, along with an app that would be a free release on the Oculus Store. However, while adoption of the Gear VR had been reported to be in the one million user range (Lee, 2016), it certainly did not have the market penetration of the iTunes App store or Google Play store. By planning to release a free version on iOS and Android as well, targeting the Google Cardboard viewer, we would greatly extend the availability of the app.

Accessibility and inclusivity were also considered. As a national museum in Canada, the VR experience is available in both official languages (English and French). To implement closed captioning in 360 degrees, captions were located every 120 degrees at a comfortable height. Working with the software team, text size and height were tested for maximum contrast and legibility. Icons and all interface elements were tested for color blindness and usability.

To facilitate visitors that may have difficulty with fine motor skills, a gaze cursor was employed as a mouse cursor. By using a time-based selector, a user simply needs to look at an icon for a few seconds to make a selection. This allowed the Gear VR version to be used hands-free once the visitor is inside the experience.

Figure 1: gaze cursor during language select

Sign language was also a consideration. Introducing video of a person performing sign language within 360 video provided a significant challenge. After thorough testing, we found that the immersion of the experience was greatly compromised, and the quality did not produce the desired result. Instead we opted to create a touchscreen version of the 360 experience that uses touch to guide the camera view. The touchscreen version allowed for greater flexibility, providing an alternative with options to toggle sign language and closed captioning on/off. Furthermore, it provides an alternative for those that do not wish to wear a headset, or cannot wear a VR headset due to medical or physical factors. Audio description of the VR experience was provided through our existing mobile app for low vision and blind users.

Figure 2: screenshot from 2D version of VR experience available on touchscreens featuring sign language and closed captions

After its initial release, we further tailored the iOS and Android version to have an optional 2D view mode similar to the in-gallery touchscreen. In doing so, anyone can experience the content on a mobile device regardless of whether they have the Google Cardboard viewer available. In this mode, users can guide the camera with their finger or turn the device and leverage the built-in gyroscope and accelerometer to change the view.

Figure 3: screenshot from iOS in Google Cardboard mode (stereoscopic) above, and 2D mode (gyroscopic) below with placement of captions

Physical design for VR: one size does not fit all

Delivering a VR experience in-gallery would identify several shortcomings of the technology in its current state in early 2016. When designing the experience, there were several operational factors to consider. Higher-end versions of VR experience such as the Oculus Rift require a tethered computer to render the necessary visuals and accommodate interactivity. Lower-end versions of VR like Google Cardboard, while effective as an easy on-boarding tool to virtual reality concepts and experiences, did not provide the level of immersion we were looking for.

Considerations were also identified regarding how to responsibly facilitate in-gallery. Visitors would need to be able to exit the VR experience immediately if they experience seizures, loss of awareness, eye strain, nausea, or any symptoms similar to motion sickness. The requirements we desired for the headset included being cordless, untethered, adaptable to multiple head shapes, allowing for visitors that wear corrective lenses, and the ability to sanitize the headset.

In evaluation of physical accommodation, the Samsung Gear VR was identified as suitable for our initial offering to deliver an in-gallery experience. Gear VR uses a Galaxy S6 mobile phone as player, and when combined with audio headphones, was a discreet, cordless device that would be easy to deploy in-gallery. It featured a central focus dial that would accommodate users with or without glasses, and further reduced the risk of eye strain. Due to the popularity of the device, third party products such as a waterproof Gear VR foam padding was used as replacement for the original Gear VR face foam cushioning. Made from a soft leather-like material, they provided the ability to clean the devices with alcohol-based wipes between uses.

Figure 4: VR headset in use

The physical constraints of the gallery itself also played a role. The section of the exhibition where this was located was approximately 320 square feet. To ensure visitors could experience the VR safely within the constraints of the exhibition space, two swivel chairs were purchased. While seated, guests could spin in 360 degrees, looking in all directions, without the danger of encountering foreign objects, surfaces, or other visitors.

Figure 5: VR station in Guatemala portion of exhibition

Along with the design of the seating, the physical exhibit needed to accommodate a locked charging station with additional units, should there be battery failure or device malfunction. Two headsets would be available at any given time during opening hours. With a life span of approximately four hours, four headsets were in regular rotation along with two spares for a total of six units. To provide access to the touchscreen version, two 12.9 inch iPad Pros paired with headphones were mounted in millwork on the wall adjacent to the seating area for the VR experience. Beside the touchscreen stations, a shelf featured Google Cardboard samples with messaging that indicated their availability for purchase in the CMHR Boutique.

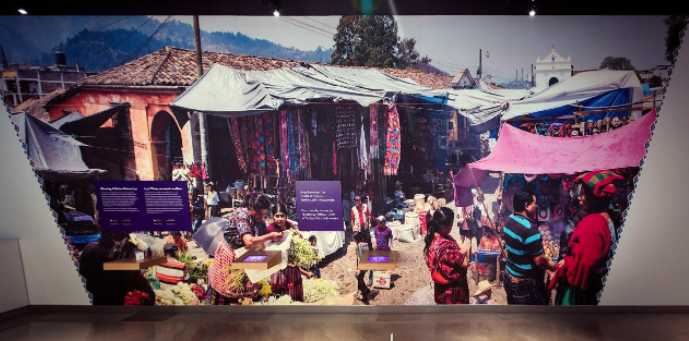

The gallery space surrounding the VR was also considered as an opportunity to prepare and entice visitors to experience the VR for themselves. The wall surface that ran the length of the Guatemalan portion of the exhibition was treated with a graphic that extended approximately seven meters wide and four meters tall. An image of one of the markets from the documentary was printed to scale to reinforce the entry and exit of the VR experience, reflecting the immersion that occurs while wearing the headset. This also provided a photo-op for visitors that wished to capture their experience while at the museum, and helped to market the experience to other visitors.

Figure 6: feature wall of large-scale graphic of the Guatemalan market. This wall also features touchscreen stations, and a Google Cardboard sample

Defining success with virtual reality

Working with the visitor services team, along with training staff and volunteers, played a critical role in delivery in-gallery. It was essential for staff and volunteers to feel comfortable and knowledgeable when it came to the technology. For 90% of staff and volunteers, this was the first VR experience they had ever encountered. Ensuring that they could pass on their comfort and enthusiasm for the experience to our visitors would contribute greatly to the success or failure of audience participation.

The exhibition design supported two VR seats available during open hours; ensuring that as many visitors as possible would have the opportunity to take part in-gallery would be a challenge for our visitor services team. With a maximum potential viewing time of 12 minutes, we achieved a turnover of a single seat every 15 mins. On-boarding of visitors was completed in under three minutes per person, including an introduction to the experience, safety precautions, and assisting the visitor in fitting the VR headset.

Visitors were informed that they could reserve a time slot at one of two locations: the main ticketing desk, and in the Level 6 gallery where the exhibition was located. There was a synchronized sign-in sheet created online that allowed staff to manage the availability of seats to ensure that walk-ups could be handled efficiently alongside reserved seats. Visitors were only allowed to reserve slots during the day of their visit.

The VR experience opened in July 2016 and closed in the beginning of January 2017. Open a total of 156 days, CMHR provided over 8600 VR experiences averaging 55 visitors a day using the two stations. To provide context to that number, on an average day the museum is open 10am to 5pm (on Wednesday nights we are open until 9pm). Over the course of an average day of seven hours, there would be a potential 28 spots per seat available, or 56 daily spots for the VR experience. In terms of demand over the course of the exhibition, the average of visitation remained constant, with only a 3% drop in usage between the first 3 months and the last 3 months.

Feedback from visitors was overwhelmingly positive. Our main challenge was the limited number of seats during the higher traffic summer months. Staff could accommodate larger crowds by directing visitors to the two touchscreen kiosk versions located near the VR stations, as well as a graphic panel that featured information on where to download the app and the availability of the Google Cardboard viewer in the boutique.

Remote audience for VR

In comparison to the in-gallery visitation, online engagement was mostly focused on a single platform. Out of approximately 3,300 downloads, iOS and Android only made up 6% and 3% respectively. Gear VR captured a niche audience 10 times larger than VR on iOS and Android. In early analysis, it appears that part of that outcome can be attributed to the number of apps available in the Oculus store versus iTunes or Google Play. In the month previous to the exhibition opening, there were only 300 apps available in the Gear VR (Oculus VR, 2016). Weaving a Better Future was featured by Oculus in an e-mail to its press contacts of new apps released. Through leveraging an emerging platform, the opportunity to have a spotlight on the project resulted in finding an increased audience and more meaningful visitor experience.

Augmented Reality

Augmented Reality (AR) shares commonalities with VR as a concept that has been around for decades (NMC, 2010). It is only within the last six years that these experiences have become more accessible and portable, due to the increased availability and capability of mobile devices. With many AR projects designed for marketing and amusement, the popularity of AR can also be attributed to location-based experiences. As with VR, the widespread adoption of AR technology has been crucial to its growth.

The ability to blend real and virtual worlds has held enormous potential for museums, and a lot has been discussed within a museum context. The 2015 Museums and the Web conference program featured eight presentations and four panels referencing AR technology (http://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/program/#2015-04-08). In the public consciousness, the success of apps such as Pokemon Go have exploded the mainstream awareness of AR, and have further expanded the opportunity for museums to embrace, extend, and innovate this type of storytelling and experience.

The CMHR’s first iteration of AR is a feature that is part of our self-guided tour mobile app, Journey of Inspiration, available on iOS and Android. Leveraging location-based information, we use it to deliver content for two distinct architectural features in the building.

In the spring of 2016, while our first VR project was underway, we decided to undertake our second AR project that would focus on image recognition. The exhibit, Freedom of Expression in Latin America (https://humanrights.ca/exhibit/freedom-expression-latin-america) uses compelling works of art, powerful personal accounts, and augmented reality technology to tell the stories of people who have used art to expose truth and motivate action. The exhibit is located in the museum’s introductory gallery.

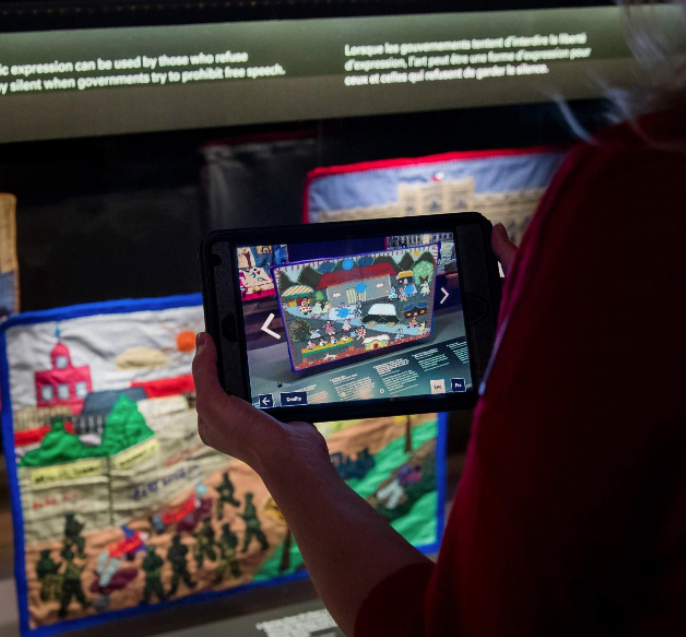

In this exhibit, augmented reality technology is used to further explore the story of Carmen Quintana, who was set on fire as a teenaged dissident in Chile and taken for treatment and refuge in Canada. Using the app Stitching Our Struggles, visitors use an iPad mini to hover over an arpillera, a vivid embroidered patchwork image containing her story, which then reveals on-screen images and text about her experiences—including excerpts from CMHR curator interviews conducted in 2016. This feature also provides visitors with exclusive virtual access to two digital artifacts (additional arpilleras) which are not physically present in gallery.

Functional design for AR

Using image recognition, the experience was based on a discreet artifact displayed in a light-controlled exhibition space. The core user-experience is to provide visitors the ability to reveal the artifact by “pulling” the arpillera from the display case. By swiping right or left, users reveal the next artifact in its place. While viewing through the app, the digital artifacts are placed in 3D space as part of the exhibit. By manipulating the device physically, you can examine the details of the artifact and reveal more information about its story.

Figure 7: AR application in use

Deployed in-gallery, the screen in portrait orientation runs an “attract” loop that invites the visitor to pick up the device. Once rotated to landscape orientation, language selection is offered and a 30 second introduction video is played. A transparent image of the arpillera appears along with instructions to point the device at the artifact, revealing hotspots that the visitor can click on. The experience is designed to last two to three minutes.

Physical design for AR

Based on user testing, the Apple 4th generation iPad mini was selected for a few reasons. Concerned with physical fatigue, the device is lightweight and can be held with one hand or two, by both adults and youth. The screen size is large enough to accommodate a shared experience between groups, and when visitors encounter an iPad, there is a low threshold in terms of their ability to be able to intuitively enter and engage in a digital experience.

When visitors arrive at the AR feature within the exhibition, they encounter a stand containing a set of iPad minis along with descriptive text. Three devices sit untethered in the rack for visitors to easily remove and return. The need for staffing in-gallery is supported with current operations and limited training was required upon deployment.

Figure 8: arpillera portion of exhibition with iPad mini and AR postcard station

Inclusive design considerations included captioned text for all media contained within the AR. This iteration of AR is a primarily visually based experience, so text-to-speech of the narrative for low vision or blind visitors is delivered via our Universal Access Points (UAP) through our self-guided tour mobile app. The UAP program is part of the CMHR’s underlying inclusive design infrastructure, and is explored in detail as part of a paper from Museums and the Web 2016 (Bahram, 2016).

Along with the in-gallery component, this AR activity lends itself well as a takeaway experience and educational asset. Postcard size images of the artifact with instructions on how to download the app for iOS and Android allow visitors to take the experience home with them. A downloadable PDF was also created for our website so that remote audiences can download and print the target image and utilize the app anywhere in the world.

Defining success with augmented reality

Freedom of Expression in Latin America launched at the end of August 2016 in our Level 2 gallery, along with the app Stitching Our Struggles. Currently we have experienced the same success as with the virtual reality. During the last quarter of 2016, the AR sessions were slightly higher than the VR, at 4,200 sessions. However, in terms of remote audience engagement, downloads of the app are currently quite low.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the latest and greatest emerging technology leads to new pedagogical approaches to the oldest and most human form of communication—storytelling. Leveraging new participatory experiences has resonated strongly with visitors, and has not only enhanced the museum narrative, but also the creation of narratives by the visitors themselves. This is the evolving museum: a reciprocal relationship between the museum and its visitors.

Using VR and AR combined with cross-media storytelling techniques as part of a layered presentation can greatly maximize and extend the visitors’ connection with museum content. Attention to interface and experience design, when successful, can bring the audience closer to the content rather than becoming a barrier. As audiences continue to seek out and participate in innovative experiences, approaching these concepts as part of an evolving toolkit for museums to tell stories is essential.

Sustainability remains an opportunity and a challenge. We continue to release applications on iOS and Android along with other selected platforms to support a bring-your-own-device (BYOD) scenario. While creating an opportunity to extend the reach of these experiences outside the museum walls, there continues to be the constraint of providing infrastructure in the form of hardware to achieve the maximum impact for on-site visitation. A question remains as to how this barrier will resolve.

Leadership within the museum in creating spaces along with the capacity to experiment with emerging technology is essential. Working closely with staff, volunteers, and partners in developing digital literacy internally will help the effectiveness of delivery of this technology. For research and curatorial staff, this is also an opportunity to engage and conceptualize how stories can be told. This is, and will continue to be, a significant challenge for small and medium sized institutions, who are limited in tangible resources, both human and financial.

As storytelling through technology continues to evolve, so does its value for museums. Like other forms of rich media, virtual and augmented reality provide a strategic opportunity in engaging our audiences. As these exciting platforms mature in personalization and adaptability, it will become increasingly important to develop methodologies for their use and implementation, and to provide enhanced digital experiences inside museums and for remote audiences.

References

Timpson, C. (2016). “The Idea Museum.” Museum Ideas Vol 3. Museum iD, 67-75.

California Association of Museums. (2012). Foresight Research Report: Museums as Third Place. Available http://art.ucsc.edu/sites/default/files/CAMLF_Third_Place_Baseline_Final.pdf

Shu, L. (2015). “Van Gogh vs. Candy Crush: How museums are fighting tech with tech to win your eyes.” Digital Trends. Published May 1, 2015. Consulted December 2016. Available http://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/how-museums-are-using-technology/

Pitt, F. (2015). “New Report: Virtual Reality Journalism.” Tow Center for Digital Journalism Blog. Published November 11, 2015. Consulted December 2016. Available http://towcenter.org/new-report-virtual-reality-journalism/

Robertson, A. (2016). “The New York Times is sending out a second round of Google Cardboards.” The Verge. Published April 28, 2016. Consulted December 2016. Available http://www.theverge.com/2016/4/28/11504932/new-york-times-vr-google-cardboard-seeking-plutos-frigid-heart

Lee, N. (2016). “Oculus highlights over 1 million Gear VR users with new content.” Engadget. Published May 11, 2016. Consulted December 2016. Available https://www.engadget.com/2016/05/11/million-gear-vr-users/

Oculus VR. (2016). Over 30 Full Games Launching with Oculus Touch this Year. Published June 13, 2016. Consulted December 2016. Available https://www3.oculus.com/en-us/blog/over-30-full-games-launching-with-oculus-touch-this-year/

New Media Consortium. (2010). Horizon Report. Available https://www.nmc.org/pdf/2010-Horizon-Report.pdf

Bahram, S., S. Gillam, C. Timpson, & B. Wyman. (2016). “Inclusive design: From approach to execution.” MW2016: Museums and the Web 2016. Published February 24, 2016. Available http://mw2016.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/inclusive-design-from-approach-to-execution/

Cite as:

Gillam, Scott. "Spotlight VR/AR: Innovation in transformative storytelling." MW17: MW 2017. Published February 28, 2017. Consulted November 12, 2021.

https://mw17.mwconf.org/paper/spotlight-vrar-innovation-in-transformative-storytelling/